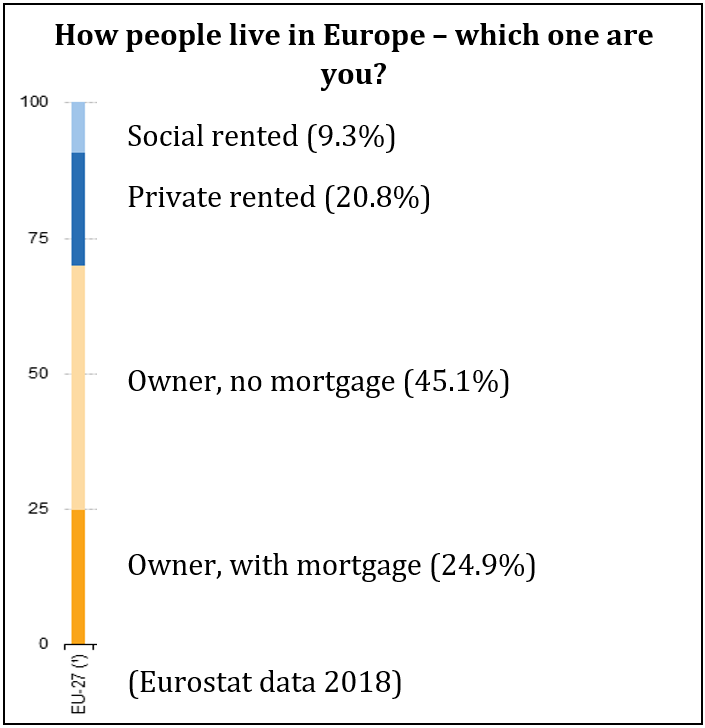

Most people in Europe own their property. Eurostat data 2018.

What’s the problem?

In the last few decades, property prices have risen faster than people’s earnings, making it unaffordable for many, especially the young, to have their own home.

For the rich, real estate is an increasingly attractive investment tool, giving rise to a burgeoning real estate market.

This double dynamic – unaffordable housing and high investment returns – has worsened social inequalities and created financial and social fragilities.

What does this mean?

For millions of families, it means that young people cannot afford to leave home. In a change from before, the majority of people in Europe aged 18-34 now live with their parents. Those wanting to move out must buy, rent or find social housing but all of these options are getting harder.

Buyers face high prices that only speculators or those with high incomes or help from their parents can afford. House prices have grown faster than incomes in all but three European countries (Finland, Germany, and Portugal) for at least 15 years. A U.K. home now costs 8x the average family income, up from 4x in the 1990s, causing home ownership among 25-34 year olds to collapse.The landlords own them now.

This is not to say that renting is cheap. This too is expensive, fuelled by people who can no longer afford to buy. In the U.K. and Spain, private rented accommodation on average now costs 39% of take home pay – perilously close to the 40% at which the E.U. considers people are ‘overburdened’ by housing costs. In fact, a quarter of private renters in Europe are now overburdened by rent, with similar trends in the U.S..

Social housing is cheaper but hard to find. Waiting lists have mushroomed as governments cut provision, especially in Belgium, Ireland, Italy, U.K. and Estonia. Even in France – the only country to build more social housing – half a million extra people joined the waiting list between 2010 and 2012.

When you add to these the impact of immigration, it’s no surprise that homelessness is rising and getting worse. Since the financial crisis, the homeless population has increased in almost all E.U. countries, doubling in Germany, Ireland, UK and Belgium.

This dysfunctional housing market makes it harder for people to relocate and live their lives. It fractures families and increases inequalities, and it diverts money from families and the real economy to banks and landlords.

How do financial markets affect this?

Housing is like protein for financial markets. Banks like to lend against collateral that they can seize when a loan turns sour; a house is perfect for this (no one can walk off with a house).

Over the last hundred years, banks have doubled the share of mortgage loans in their lending portfolios from 30% in 1900 to about 60% today. But the party really started only when bank regulations were relaxed in the 1980s. Over the next three decades, banks doubled the amount of mortgages relative to the value of the housing stock. The result? A mountain of private debt and a prolonged house price boom (with occasional busts) which continues today.

Add to this the credit cycle – in which banks lend more when house prices rise, and house prices rise when banks lend more, and the same in reverse – and you can see why, of the nearly 50 systemic banking crises in recent decades, more than two thirds were preceded by boom-bust patterns in house prices. Real estate credit is now an important predictor of financial instability.

How does this affect you?

Real estate credit should also be a predictor of social instability. One of the most striking images from the financial crisis was probably that of home evictions in the U.S., in Spain or in Hungary, with hundreds of thousands of families pushed out of their houses and left with no place to live but the streets – or a car.

Residents in most big cities can only watch as corporate and foreign investors buy up land for office blocks, shopping malls and luxury homes, while the original residents are slowly excluded. And many investors use shell companies or tax havens to manage the proceeds.

For instance: The transformation of an old railway line in West Chelsea in Manhattan into a public walkway and park has attracted wealthy investors to a mixed income neighbourhood, radically transforming it with luxury housing units costing in the multi millions, and displacing longer term residents.

Financialisation means that housing is no longer about making homes and communities. In the U.K., where housebuilding executives are among the best paid in the country, the quality of newbuild houses is staggeringly poor. Financialisation has encouraged local authorities to sell public land to the highest bidder, instead of looking at it as a social good.

What’s the way forward?

- MAKE FINANCE A SERVANT, NOT A MASTER. Society must actively shape the financial system to serve its needs. The size, scope and structure of the financial sector cannot be left to market forces or oligarchic elites on their own. The financial system should create and allocate credit and capital in line with society’s needs.

- LESS PRIVATE DEBT. Society should be less dependent on the creation of private debt and money. Credit regulation should aim to prevent over-indebtedness and credit-fuelled speculative bubbles.

- INVESTING NOT BETTING. More useful investment for socially and ecologically sustainable activities; less ‘casino’ financing for short-term, unproductive and speculative activities. More relationship-based finance.

Sign up to keep the impacts of financial crises out of your home.

Sources

Why You Can’t Afford To Buy A House And How To Fix It | Laurie Macfarlene, Youtube/TedxTalks

The State Of Housing In The EU 2015, Housing Europe

Si Se Puede: 7 Days At PAH Barcelona, Youtube/ Comando Video

The Great Mortgaging: Housing Finance, Crises, And Business Cycles, The National Bureau Of Economic Research

Also check out

This really great infographic by The Visual Capitalist on how Vancouver’s housing crisis drove them mad

And while you’re at it, watch Christian Bale, Steve Carell and Ryan Gosling in The Big Short