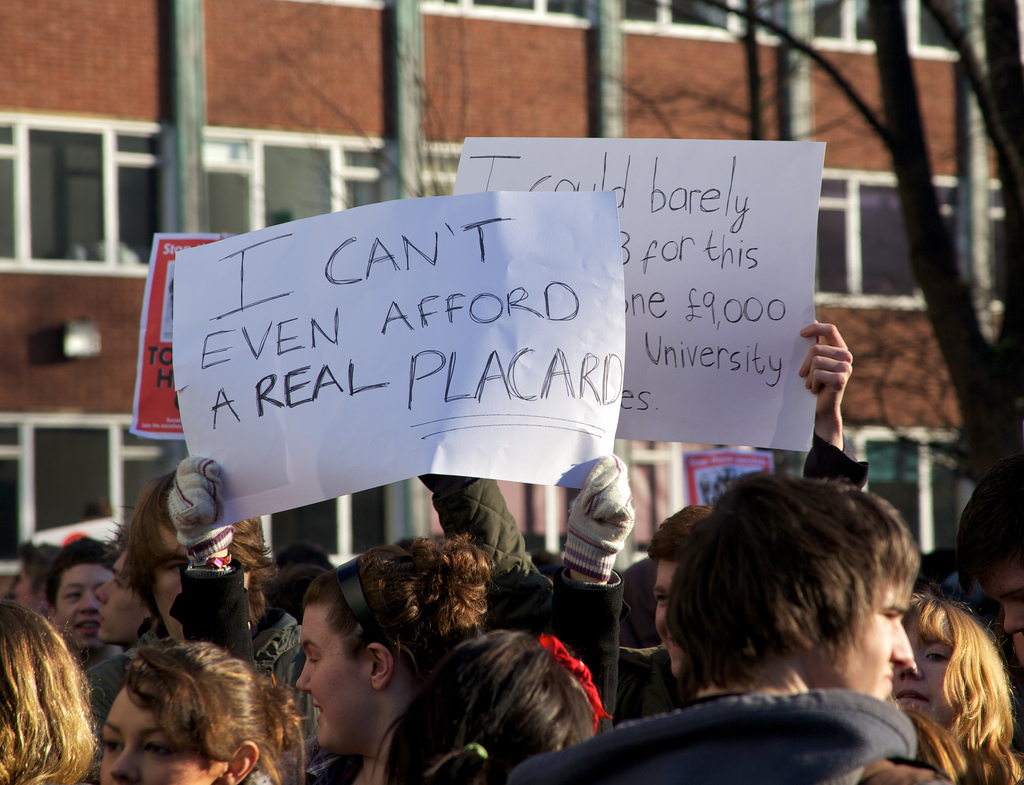

Photo by Pete Birkinshaw on Flickr

What’s the problem?

For a few decades now, the cost of higher education has been progressively switched to students through increasing tuition fees and decreasing public grants. The result is a boom in student debt that is carried mainly by young people.

US graduates typically leave university with $34,000 in student debt, up nearly 70% from 10 years ago. Some leave with much more – stories of people graduating with $100,000 or more of debt are easy to find…

Andrew Kirk, 29, is a geography teacher in Dallas, approaching his fourth year of teaching. He holds both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history. When Kirk started teaching, he had close to $150,000 in debt.

The former chair of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, told the US Congress that his son was on track to leave medical school with $400,000 in debt.

This hits the poor hardest. People from poorer backgrounds already struggle to cope with a heavy debt burden, but these additional tuition fees can worsen inequality and damage social mobility – the opposite of what education is meant to achieve.

What does that mean?

This mountain of student debt ($1.5 trillion) acts as a drag, not only on individuals but also on the economy. Graduates with high debt live with their parents for longer, they’re slower to buy a home, they get married later, they have children later and save less for retirement. They are less likely to start a business and they have less money to spend on everyday things.

All the while, people are being educated for longer, costs are rising and governments are cutting back. This is where the private financial sector is “filling the gap”.

But the financialisation of education – led by the US – has revealed side effects that are just as bad – teacher shortages, crippling student debt, rip-off private financing, and a tendency for financial outcomes to overshadow the other goals of education.

Each country approaches education in its own way, it may be time to ask: how far do we want to let finance rule the classroom?

How does finance affect it?

Finance is often a beneficiary and cheerleader of bad trends:

- Financial decisions taken by universities

Universities are turning to debt and derivatives to fund themselves. A shocking study by The Roosevelt Institute in 2016 found that a group of US colleges had paid more than two billion dollars to banks after taking bets on interest rates that went sour.

In the UK, university debt is soaring as colleges invest to compete and attract students. Investors and bankers expect the government to step in if a university gets into trouble to prevent private lenders from taking a loss, but some colleges are already borrowing more than they can repay and the credit rating agencies are starting to worry. UK university debt has tripled in the last ten years.

Meanwhile, some university bosses are being paid like bankers. The Vice Chancellor of the UK’s University of Bath, Dame Glynis Breakwell, was criticised in Parliament after earning £451,000 in 2016. In the US, the University of Louisville’s President, James Ramsey, was paid ten times as much, taking home $4.3 million in 2017. The president of Harvard, Drew Gilpin Faust, earns around $1m a year on average.

- High costs & student debts

At the other end, student debt has more than doubled – from 3.5% to 7.5% of US GDP between 2006 and 2016. Banks earn fees from securitising student loans, and debt collection agencies profit when people default. In fact, delinquency rates on student loans have doubled between 2003 to 2012!

- Low salaries & teacher shortages

Ironically, one of the biggest impacts of the student debt mountain is on education itself. High Student Debt + Low Teacher Pay = Shortage of Teachers. In 1994, a teacher in a US public school could expect to earn almost the same as any other professional. But by 2015, teachers were earning 17% less than classmates who took jobs in other sectors. Aggravated by the financial crisis, the teacher pay gap is now between 6% and 22% in OECD countries.

Plus, public funding cuts mean that teachers today work longer hours with fewer resources, often under extreme pressure leading to stress and burnout. Perhaps this is why US teachers pay more for health insurance than other government workers.

Because of this, the US saw a 35% drop in teacher training applicants after the financial crisis – a loss of 240,000 potential recruits. The same is happening elsewhere; in Sweden, nearly half of all teachers are now aged over 50. If these trends continue, what will happen to the state of our education system when our teachers retire?

- Privatization & tax-payers

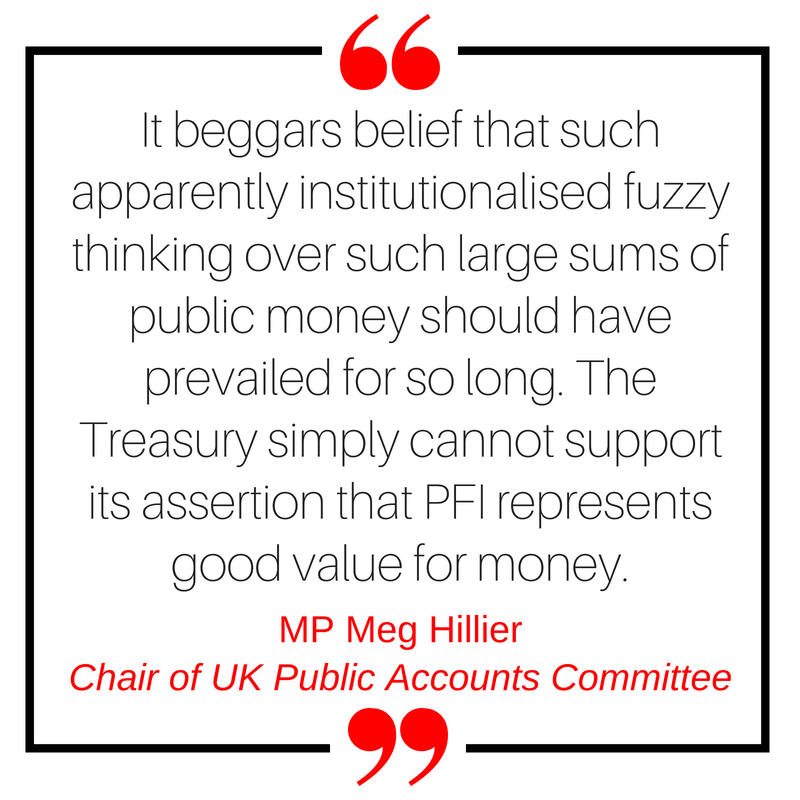

Where there is a push for privatisation, finance is usually not far behind. One of the worst examples of this is the UK’s private financing initiative (PFI).

The UK has used private funds for public infrastructure projects (like schools and hospitals) since the 1990s. These projects are accounted “off the public balance sheet.” The costs do not have to be categorised as public debt – even though the government is ultimately still responsible if things go wrong.

The ongoing costs of PFI to the taxpayer have been high and the contracts inflexible, with schools having to sell off land to repay debts, cut corners on building safety standards, or pay for empty buildings for years on end.

To add insult to injury, around half of the equity financing for UK’s PFI schemes has been bought by investors in tax havens who pay little tax and are increasingly remote from the public services being delivered.

The UK might now be learning its lesson; there are very few new PFI contracts being signed in the UK.

PFI in action:

- Liverpool City Council is paying £4 million a year for an empty school, which will see almost £55.5 million of taxpayer funds wasted since the school became empty in 2014.

- 17 PFI-funded schools in Edinburgh were closed in 2016 after 9 tonnes of masonry fell off an external wall at Oxgangs Primary School due to basic defects in the construction. A public inquiry found that the PFI financing had increased the risk of poor quality design and construction.

- Future-focused curriculums

Education is increasingly being rated according to graduate’s future earnings, for example with the current UK government’s focus on value for money of university courses. Under this approach, it’s more valuable to educate hedge fund managers than nurses or scientists! This way of looking at things completely misses the wider benefits of education, including social mobility, research and innovation, or having a well-balanced economy.

What this means for you

Education can be seen either as a public good or as a private service. Which view comes to dominate depends a lot on how education is financed. The more that education is financed through private debt, the stronger the “private service” viewpoint will become. The public good aspects – including giving everyone a fair chance and developing a well-balanced economy – become easier to forget.

An over-financialised education system will saddle young people with debt and fewer people will become the teachers, nurses, entrepreneurs and parents of tomorrow.

As the academic Michael Sandel noted, markets don’t only allocate goods, they also express and promote certain attitudes towards the goods being promoted. This applies to finance as much as to education.

What is the best way forward?

- LESS FINANCIALISATION. Society must become less dependent on the private financial sector to access basic needs such as housing, health, education etc., and the role and size of private finance should be reduced more generally.

- LESS PRIVATE DEBT. Society should be less dependent on the creation of private debt and money. Credit regulation should aim to prevent over-indebtedness and credit-fuelled speculative bubbles.

- FIGHTING INEQUALITY. Financial services should be designed and regulated to reduce their contribution to discrimination and inequality.

Feeling newly-educated about finance?

Sources

Education at a Glance OECD, 2017

The Intersection of Student Loans and Social Class: Exploring Borrowers’ Journeys into Debt and Repayment, Elissa Chin Lu, 2016

U.S. Teacher Shortages—Causes and Impacts, Learning Policy Institute, 2018

Short-Sellers: Watch The Student Loan Market, LIME Brokerage, 2015

The Financialisation of Higher Education, Roosevelt Institute, 2016

Treasury must set out clear position on PFI, UK Parliament, 2018

‘What Money Can’t Buy, The Moral Limits of Markets’ a book by Michael J. Sandel