By Guérin Nicolas from Wikimedia Commons

What’s the problem?

We are likely entering the Earth’s 6th mass extinction event (the Holocene or Anthropocene extinction). The last such event, 65 million years ago, saw the end of the dinosaurs, clearing the way for mammals and humans. Unless we take radical action very fast, we face the extinction of thousands of species already under threat – and humans are at risk too.

What does this mean?

You’ve probably heard that bees are dying at an alarming rate: commercial honey bee populations in the EU have decreased by 25% since 1985, and by 45% in the UK since just 2010. Yet up to a third of our food depends on pollinating insects such as honeybees. German scientists found the ‘abundance of flying insects has plunged by three-quarters over the past 25 years.’ Each year more large mammals, such as rhinos, are declared extinct. But the problem is much broader and much more serious.

© Hans Hillewaert

The World Wildlife Fund’s (WWF) Living Planet Index shows ‘global populations of fish, birds, mammals, amphibians and reptiles declined by 58 per cent between 1970 and 2012; including a staggering 81% drop among freshwater populations. Ocean life is dying due to overfishing and the acidification of the waters. We are reaching a level of carbon dioxide in oceans that has not been seen in 14 million years.

Food for thought

Many elements of 21st century capitalism are causing a catastrophic loss of biodiversity. For example, industrial farming aims for intense monocultures (of plants, animals or fish) to maximise profits from a single commodified life-form. They suppress natural biodiversity by opting for chemicals, genetic modification, highly selective breeding and energy-hungry machinery.

Meat production especially is at the core of the problem. Cattle ranching accounts for 80% of deforestation in the Amazon – one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. The conversion of the American plains to cattle production has greatly reduced biodiversity too. In fact, the US could feed 800 million people with the grain grown to feed livestock.

This global crisis of biodiversity threatens our humanity: species are disappearing and diminishing at an alarming rate – and finance is implicated.

What do financial markets have to do with this?

By opting for monocultures, such as the one on the American plains, farmers (and other firms in the food chain such as Monsanto) can satisfy the overconsumption of today’s society, and the financial system’s requirement to maximise shareholder value. This is both hugely energy-inefficient and highly risky, not to mention disrespectful towards the lives of other species.

Despite the benefits – natural processes, more nutrients for less energy, ecological stability, flourishing biodiversity – we have yet to move to agroecological systems, such as permaculture and food forests (agroforestry) in a mainstream way. In fact, instead of curbing industrial farming and food production activities that harm biodiversity, financial markets encourage them.

Food and agriculture is indeed a big example of the ways in which 21st century capitalism puts short-term profit before long-term efficiency and stability, but it is not the only culprit.

Planned obsolescence in our phones, computers and cars requires mining of vast amounts of rare earth material leading to habitat destruction.

Logging, transport, infrastructure development, residential and commercial development, energy production, the fragmentation of rivers and streams, the abstraction of water- these are some other examples of activities that diminish the ecosystems on which many species depend.

The truth is that financial markets are extremely bad at dealing with costs that appear after investors have taken their short-term profits, a problem known as the tragedy of the horizons. They are even worse when the costs fall on other people or on the environment, known as externalities.

From the burning of fossil fuels to dumping plastic in the oceans, it is no secret that pollution is disrupting the Earth’s ecosystems. And as manmade climate change speeds up, it does not afford species and ecosystems the time to adapt. These disruptions also affect the migratory patterns, feeding habits and the breeding of several species.

And still, the financial system’s focus on short-term profits actively discourages the food, mining and other industries from long-term thinking and conservation.

It doesn’t have to be like this

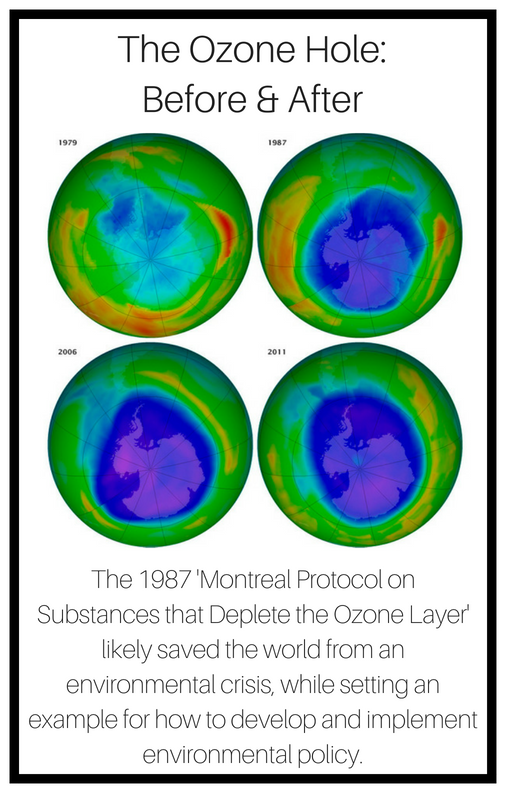

We have corrected environmental mistakes in the past. Remember the hole in the Ozone layer? It’s now recovering, thanks to a worldwide ban on chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). For biodiversity, there have been numerous local projects to clean up quarries, restore wetlands, re-wild or reintroduce species – many of them motivated by a mix of longer-termism and financial or regulatory considerations.

With the right incentives, the financial system could reward companies that buy their ingredients from responsible sources and penalise the ones that destroy habitats and hurt biodiversity. Comparison tools such as the Palm Oil Scorecard already help investors and consumers to choose sustainable companies (palm oil is found in products from margarine to lipstick but growing it irresponsibly can lead to massive deforestation and loss of wildlife).

The amazing power of nature to regenerate itself should inspire businesses and finance to work with it, not against.

Biodiversity can be restored in unpredictable ways, as this famous video about the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone Park shows.

Finance has a big role to play if we demand it: we could update our accounting methods to reflect environmental impacts; we could lower the cost of capital for countries that reduce their environmental liabilities; we could reward companies that invest to reduce their water risk; and many other ideas.

Through a mixture of carrot and stick, strict limits and fresh thinking, there is no reason why finance should not become a guardian of nature, instead of a burden on it.

What it means for you

You can do a number of things to fight biodiversity loss: conservation and continued awareness is key. Being conscious of what you eat and purchase, conserving energy at home, using public transportation, recycling, participating in land preservation, promoting education and contacting elected officials- all these steps count.

With finance, at the moment, it’s hard to know if your bank, pension fund or insurance company finances activities that destroy biodiversity. But if you are aware of what financial firms are up to, you will be able to switch away from such firms with ease. For this, we need to demand simple, transparent and ethical financial instruments.

The financial system itself resembles a monoculture at the moment – dominated by oligopolistic giants that think and act the same – so we should encourage new kinds of financial institutions- such as alternative and public financial firms that can promise ethical lending and investment, not simply maximise investors’ short term profits.

Consumer action alone will not be enough, the key solutions mostly lie in policy. We need to elect politicians who will protect the invaluable biodiversity of the planet and take steps to see that it grows and flourishes. Ultimately, governments need to enact stronger, scientific ecosystem protection laws, and the Conference of the Parties (COP2020) will hopefully be a turning point.

We need a fresh approach that makes finance serve society and nature, by investing and lending to projects that protect and increase biodiversity before it is too late.

What’s the way forward

- Saving our planet: A massive divestment/investment shift should allow our societies to go back within planet boundaries, starting with avoiding catastrophic climate change. Central banks should play a more active role by aligning their policy with long-term society needs.

- Investing not betting: More useful investment for socially and ecologically sustainable activities; less ‘casino’ financing for short-term, unproductive and speculative activities. More relationship-based finance.

- Make finance a servant, not a master: Society must actively shape the financial system to serve its needs. The size, scope and structure of the financial sector cannot be left to market forces or oligarchic elites on their own. The financial system should create and allocate credit and capital in line with society’s needs.

- Transparency: Citizens should easily access information and data about the financial sector and its evolution – including the actual impact of regulation. Financial firms should disclose what they are financing and how much they are charging.

- Diverse Ecosystem: The financial sector should be diverse and include more stakeholder, public, mutual, cooperative and other types of institution. It should not be dominated by very large firms with similar business models.

We share our world with many. It's time to stand up for our planet.

Sources

The Role of the Bee, Greenpeace

Palm Oil Buyers Scorecard, World Wildlife Fund

Climate Change and the Cost of Capital in Developing Countries, UN Environment

The Water Risk Filter, World Wildlife Fund