Photos by Alan Stanton on Flickr and Sarahmirk on Wikimedia Commons

What’s the problem?

For decades we have been told that ‘a rising tide lifts all boats’ – that when the richest do well, everybody benefits. But today, the richest 1% own more than the other 99% put together.

Photos Brian Cassey, Pxhere

Things are getting worse: last year, 82% of new wealth created went to this top 1%, with the bottom 50% getting nothing at all.

It’s now clear that our economy only seems capable of enriching a few, leaving most people behind. This spiraling economic inequality is one of the greatest global crises of our time.

What does that mean?

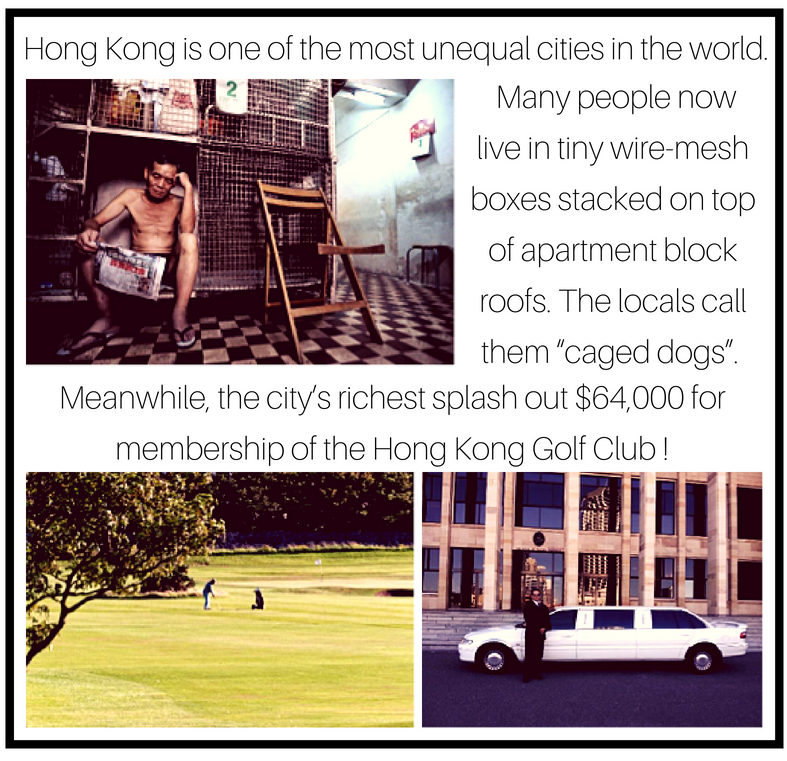

International inequality – between rich and poor nations – remains a huge problem. But what’s new in the past few decades is that inequality is also rising within almost every region of the world, including the richest. In the US, the share of the pie going to the bottom 50% almost halved between 1971 and 2014 – from 20.3% to 12.6%. At the same time, the share going to the top 1% almost doubled, from 11.1% to 20.2%. It’s been a similar story in the UK. In absolute terms, most ordinary people in these countries aren’t getting better off.

Since the financial crisis, this trend has only accelerated. Over the last decade, ordinary workers’ incomes have gone up by just 2% a year on average, while billionaire wealth has gone up by 13% a year.

There are two main drivers of rising inequality:

- The share of prosperity going to workers in the form of wages has consistently fallen, while the share going to owners of capital has risen.

- Pay inequality is increasing – with lower paid workers bearing the brunt of stagnant wages, while top earners increase their share.

What this means is this: Ordinary people are being hit twice – they’re getting a smaller slice of a shrinking pie.

How do financial markets affect this?

The explosion of inequality has coincided with the explosion of the financial system. After its deregulation in the 1980s, financial assets expanded to many times global GDP.

Some of the impacts are easy to see: Flows of ‘hot money’ around the world have contributed to financial crises and massive inequality in countries such as Argentina; banks have played a role in enabling global tax avoidance. But financialisation is driving inequality in deeper ways than this…

1. Outsized profits for banks: In the UK, financial corporations’ share of all corporate profits leapt from around 1% in the 1960s to 15% after the crisis. In the US it’s a similar story: this figure soared from around 14% in the 1960s to around 37% in the early 2000s.

2. Outsized pay for top executives: Nearly ¾ of the rise in top pay can be attributed to the bonuses paid to a few top bankers, financiers and chief executives. In Europe, around 5000 bankers earn more than €1 million a year! This in turn has ratcheted up the pay of executives at other companies, who benchmark themselves against their financial counterparts. Financialisation has also driven up top-pay indirectly as chief executives are rewarded with stock options for doing things that boost the share price.

3. Wealth extraction, not wealth creation: But it’s not only banks’ own profits that are the problem – it’s also the way they make these profits. Whether it’s sub-prime mortgages or commodity speculation, finance is less and less about investing in the economy, and more and more about creating new financial assets and betting on their future price.

This is a zero-sum game: it is not creating wealth, but extracting it from others in the economy. In other words, fuelling inequality is part of global mega-banks’ DNA.

It tends to be the wealthiest who have most access to these assets – and, as Thomas Piketty famously argued, the returns on their investments will tend to outstrip economic growth. So financialisation means more opportunities for the richest to turn money into more money – while the poorest pick up the tab when bank gambles fail.

4. A debt-inequality spiral: As ordinary people’s wages are squeezed, people increasingly turn to loans to plug the gap in their wages. And banks are only too happy to encourage them. Personal debt is on the rise everywhere, and in many countries it is now more than 200% of their GDP! Not only does interest from these piling debts transfer wealth directly from the poorest to the richest, but because the poor are charged higher fees and interest rates they are pushed even deeper into the toxic cycle of debt (and they’re unable to repay their borrowings). Such vulnerabilities in the system are exactly what led to the 2007 sub-prime crisis in the US.

How Debt Interest Feeds Inequality, by Positive Money

5. Crisis → Bail-outs → Austerity: the massive bank bail-outs that followed the financial crisis transferred billions of dollars from ordinary taxpayers to the world’s richest corporations. The austerity that follows makes sure that the poorest in society pay the price for it. Within the eurozone, the losses of French and German banks were effectively transferred to the poorest parts of the poorest populations in Europe (most catastrophically in Greece). And when public services were slashed, it disproportionately impacted the ones who relied on them most.

How does this affect you?

By its very nature, we are all affected by this toxic spiral of financialisation and inequality. If we are struggling to make ends meet and get into debt, our money is sucked up by the financial system through interest payments. Even if we consider ourselves well off, we are probably subsidising finance through our mortgage payments, or the fees we pay on pension savings and insurance products. If we pay taxes or use public services, we are still paying the price for the global banking crisis. And as citizens, we all lose out from rising inequality and the strain this puts on our social fabric.

Ten years after the crisis, none of these problems have gone away. Many countries are still relying on debt to sustain their economies, leaving their citizens with a ticking time-bomb. We can only create a more equal society if we fix our broken finance system.

What’s the way forward?

- FIGHTING INEQUALITY. Financial services should be designed and regulated to reduce their contribution to discrimination and inequality. Tax havens should be closed havens are closed, debt relief should be is made possible for over-indebted countries. A fair taxation system should redistributes wealth from the 1% to middle and working classes and from large corporations to the public purse.

- ACCOUNTABLE FIRMS. Financial firms should be accountable to their stakeholders, from customers and employees to local citizens. For example, asset managers would engage with savers; banks would include more stakeholders on their boards; and the banking sector would include more stakeholder and public banks and institutions.

- DIVERSE ECOSYSTEM. The financial sector should be diverse and include more stakeholder, public, mutual, cooperative and other types of institution. It should not be dominated by very large firms with similar business models.

The average person is suffering, getting a smaller piece of a shrinking pie. You can help put a stop to this by clicking here.

Sources

Reward Work, Not Wealth, Oxfam

An Economy for the 1%, Oxfam

Crisis Monitoring Report 2015, Crisis Europa

Inequality and Financialisation: A dangerous mix, New Economics Foundation

Also check out

Watch:

David Harvey’s 2010 video, ‘Crises of Capitalism’, Youtube/RSA

Read:

- Yanis Varoufakis, ‘And The Weak Suffer What They Must?’ – an inside account of the Eurozone crisis and its impact on Greece

- Nicholas Shaxson, ‘Treasure Islands’ – an exposé of the role of finance in global tax avoidance

Explore:

- World Inequality Database – lots of interactive maps, charts and graphs to explore

- IMF statistics on the rise of debt