What’s the problem?

Population growth, agricultural trends and climate change have put a serious strain on the global water supply. Already more than 90% of our freshwater consumption is from the agricultural (70%) and industrial (20%) sectors, leaving a meager 10% for the world’s 7.6 billion people to use domestically.

1 in 4 people on the planet don’t have access to clean drinking water, and nearly half the global population is already at risk of water stress at least one month per year.

What does that mean?

The world is running out of water. In fact, fresh water is quickly overtaking crude oil as the scarcest critical resource. This shapes not just our environment and economy but geopolitics as well. The U.N. has warned that water scarcity can lead to civil unrest, mass migration, even wars.

As the supply of water decreases and demand increases, the price skyrockets. Water is an increasingly attractive “asset” for businesses to invest in, with water privatization leading to tariff wars. In Belgium, water prices rise by 4% nearly every year. In the U.S., municipal water prices in 30 cities increased by 18% since 2010 and by 7% in 2017-18 alone. In Pakistan, the market for bottled drinking water has grown three-fold, and will reportedly grow four-fold by 2021. As it stands, a litre of Fiji water anywhere in the world costs more than a litre of petrol and a litre of milk combined.

How do financial markets affect this?

Today, the world looks at water not as a free property and the right of every individual, but as a money-driven commodity like the stuff we dig out of the ground. Disturbingly, one of the immediate measures that European financial institutions asked Greece to take when the country was adopting austerity policies was to sell off €50 bn worth of public “assets”, the first of which was privatizing water. Water privatizations have become common, despite fears that private ownership can mean higher water prices.

A U.N. study tried to put a price on the damage caused by water abstraction by the world’s largest (mining, energy, industrial, etc.) companies and they reckon it’s equivalent to $366 billion per year! Private investors are reluctant to cough up the money for this environmental depletion, but this will have a financial cost eventually. Extreme droughts could increase losses in some investment portfolios 10-fold, reducing agricultural productivity for years afterwards. A serious water shortage could add billions to a country’s borrowing costs; an actual water crisis could cost much much more.

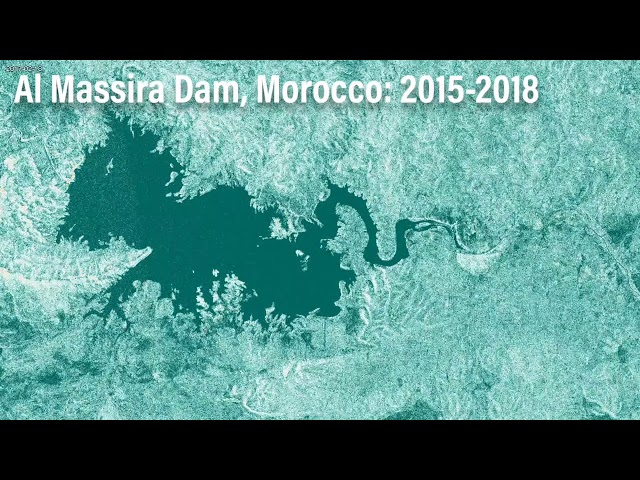

Global trade can make the problem worse. For example, the world’s 5th largest producer of strawberries, Morocco, sells 95% of its production to Europe, effectively exporting water through its agriculture. This exacerbates Morocco’s water problems. Their reserves are drying up from a combination of climate change and agriculture, putting it at risk of a “Day Zero” water shortage, similar to the risk faced by South Africa.

This map shows just what’s happening to Morocco’s Al Massira Dam that supplies water to Casablanca

It doesn’t have to be like this.

Finance providers could look for innovative ways to invest in water, such as reviving sources, developing natural underground water storage (aquifers), or using wetlands to deal with industrial waste. In New York’s watershed protection programme, city-dwellers cut the costs of flood-protection by paying farmers to conserve forests and wetlands.

Yet these so-called ‘nature-based solutions’ account for less than 1% of today’s water infrastructure investments, and total water investment is only a third of the $1.7 trillion needed to provide safe drinking water for all by 2030. There is still a lot that could be done.

What this means for you

As water gets scarcer and increasingly privatized, the cost of drinking and consuming water has increased, and related industries – like agriculture and food – have increased their prices too. Data shows that rising food prices in 2010 drove some 44 million people into extreme poverty. Will water be the next cause?

But there’s a silver lining. Several European cities (especially in France, Spain and the US) are reclaiming control of their water from private companies, while investors are taking care to invest with firms that take the environment seriously. The solution lies in you.

What’s the best way forward?

- LESS FINANCIALISATION. Society must become less dependent on the private financial sector to access basic needs such as housing, health, education etc., and the role and size of private finance is to be reduced more generally.

- MAKE FINANCE A SERVANT, NOT A MASTER. Society must actively shape the financial system to serve its needs. The size, scope and structure of the financial sector cannot be left to market forces on their own. The financial system should create and allocate credit and capital in line with society’s needs.

- FINANCE THAT SAVES OUR PLANET. A massive divestment/investment shift should allow our societies to go back within planet boundaries, starting with avoiding catastrophic climate change. Central banks play a more active role by aligning their policy with long-term societal needs.

Do you want to fight for “remunicipalisation”?

Sources

Survey Finds World Water Rates Rising, Waterworld

Use Of Freshwater Resources, European Environment Agency

The Great Greece Fire Sale, The Guardian

Al Massira Dam, Morocco: 2015-2018, World Resources Institute

Also check out

This great interview by Sakoto Kishimoto (Transnational Institute) in which she talks about the forces that are driving the reclaiming of public services like water

This PWC blurb on how New York managed to keep it’s drinking water supply clean and protect the environment

Yorgos Avgeropoulos’ movie “Up To The Last Drop: The Secret Water War In Europe”