Photo by Alan Stanton on Flickr

What’s the problem?

The advanced social system and welfare state that was developed after WW II is in danger: during the last decade, social protection – pension schemes, unemployment allocation, etc. – has been attacked in several countries.

Meanwhile, the dynamic of high unemployment levels remains in operation in many European countries, despite a decreasing trend since 2013. Working conditions are also getting worse. Working hours are increasing, and so is the pressure on wages.

And finally, the double blow of cuts in government spending and privatization means that basic public services are becoming less and less affordable.

What does that mean?

Following the financial crisis of 2008, huge amounts of public money were used for banks’ bailouts. Consequently, public debt increased, and austerity policies flourished in an attempt to restore a balance in public budgets. These policies reflected similar measures in many countries: reduction of public investments, non-replacement of retired civil services employees, wage moderation, longer working hours, tighter rules for unemployment and other social benefits, and increase of retirement age.

And they’ve had broad consequences:

- Reduced funding of public services – including the reduction of the number of civil servants – added to the depressed economic conditions and the massive increase of unemployment, especially among the youth (close to 20% unemployed in 2016 in EU 28).

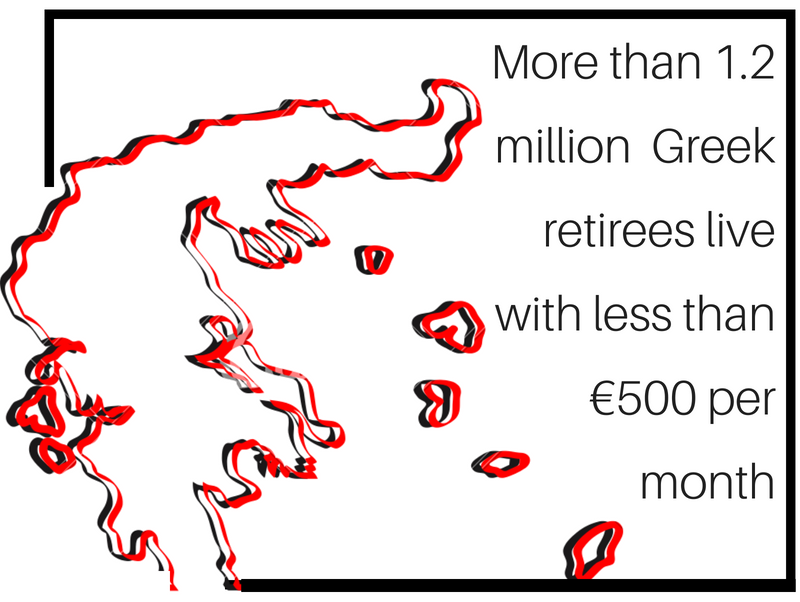

- Contraction of the welfare state led to a higher risk of poverty for the unemployed, deteriorated the living standards of workers, and increased health hazards among the population. Ironically, at a time when social aid was needed most, millions of people were kicked out of their homes and couldn’t pay for their mortgage loans anymore. In Europe, Greece is probably the most dramatic example of such policies imposed by creditors.

- Contraction of public expenditures and the moderation of wages reduced people’s purchasing power, and in turn the demand for goods and services. This led to a general decline in economic activity, bringing down GDP growth and increasing the ratio of indebtedness.

- Throughout all this, the continuous quest for higher profits by companies led to further pressure on working conditions and more suffering at work, generating a vicious cycle: work-related stress reduces productivity and induces an increase of healthcare cost for social security, hence undermining the “efforts” towards economic growth and balance of public accounts.

Whatever the way we look at it, the explosive cocktail of squeezed workforce and austerity policies seems to be everything but successful.

How do financial markets affect this?

Financial markets bear an important responsibility in this situation: on the increase of unemployment rates, on the worsening of working conditions, and on the dismembering of social protection.

- Banks & financial institutions tightened lending: After the crisis, the very same banks that were saved from bankruptcy by public money started to tighten their lending conditions, hence reducing the available capital to sustain economic activity and led to this so-called “credit crunch”. Because of this, small and medium sized enterprises (SMB) – which are major employers in Europe – could hardly hire any more workers.

- Big companies favored short-term profits over long-term impacts: For the last three decades, the maximization of shareholder value has led big companies to relocate their activities in regions of lower social and environmental standards, leaving thousands of people unemployed. These short-term decisions are sometimes encouraged by “activist hedge funds’’ (funds that make large enough investments in a company to control management and decisions). Since corporate executives’ compensations depend on the yearly shareholder returns, they’re driven to only think of short term gains, thus widening the wage gap.

- Free trade agreements undermined public interest: Free trade agreements that are currently being negotiated make provisions for companies to sue states if they implement social, fiscal or environmental policies that go against their interests (a.k.a. dispute settlements). It also gives companies scope to influence regulations ahead of the process (a.k.a. regulatory cooperation). All this simply undermines the representation of the public interest in financial regulation.

Under all these conditions, the bargaining power of wage earners is weakened, and this is why their working conditions are getting worse.

But there’s more. The willingness to tackle unemployment and to keep up with international competition has led governments to lower social protection and labor law standards in order to attract companies: longer working hours, delayed age of retirement, ‘flexibilization’ of employment conditions and contracts, etc. all point to the same direction. Workers become the variable for adjusting companies’ profits. At the same time, the right to strike is being undermined on several occasions, and essential social benefits and services experience regular cuts.

But how could such policies have been set up? Part of the reason is that the financial and business lobbies have become so powerful.

As major creditors of governments – banks, investment funds, hedge funds and insurance companies – financial institutions and influential lobbies can dramatically influence public policies, public expenditures’ choices and regulation. Especially in a context where several countries renounced their ability to finance their activities through their central banks.

How does this affect you?

Virtually everyone is concerned by this ongoing process: from civil servants to SMB employees, from the unemployed to beneficiaries of social aid, from students to retirees. It is crucial to understand that our interests are converging in one direction: to demand a social and environmental regulation of financial activities, and to protect the welfare state that made the progress of our living conditions possible.

The crisis could have been an opportunity to change the rules of finance, to support the needs of all people. Yet few major changes have occurred, and the major reforms have come down to lowering the standards of social programs, public services and employment laws. This will keep on creating more social unrest and injustice unless tackling the crisis’ social cost is made a political priority.

What’s the best way forward?

- LESS FINANCIALISATION. Society must become less dependent on the private financial sector to access basic needs such as housing, health, education etc., and the role and size of private finance should be reduced more generally.

- FINANCE THAT’S SAFE FOR SOCIETY. The financial sector should be less interconnected and its firms able to absorb their own losses. No private firm should be too-big-to-fail.

- ACCOUNTABLE FIRMS. Financial firms should be accountable to their stakeholders, from customers and employees to local citizens. For example, asset managers would engage with savers; banks would include more stakeholders on their boards; and the banking sector would include more stakeholder and public banks and institutions.